Opening hours: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm, closed on Sun, Mon and Public Holidays

Exhibition Press Release >>

MORIMURA Yasumasa CV >>

MORIMURA Yasumasa Works and Information >>

Opening hours: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm, closed on Sun, Mon and Public Holidays

Exhibition Press Release >>

MORIMURA Yasumasa CV >>

MORIMURA Yasumasa Works and Information >>

What kind of art does Morimura Yasumasa make?

Morimura is a Japanese artist who deals subjectively with his origins in the Showa era and the 20th century. After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan fell under the influence of Western civilization and culture, and after the Pacific War, the country was strongly affected by American civilization and culture. And in ancient times, Japan deeply immersed itself in Chinese civilization and culture. Morimura’s artistic pursuits are closely related to the Japanese mentality, rooted in the historical acceptance of a succession of different cultures. This sheds some light on his intentions and his approach of grounding his work in the spirit of the times and the spirit of history.

Morimura continually strives to become something other than himself, and his art is an accumulation of acts that question the meaning of the self. By supplementing his work with unique analyses of other people, and the art and historical events associated with them, Morimura’s use of his own body in his photographs, videos, and performances suggests that his art is more than the resultant work, and that the site itself plays an important part in his practice. This is borne out by the fact that he goes to great lengths to convey the atmosphere of the place.

This exhibition traces the 34-year trajectory of Morimura’s art through a collection of Polaroid-style photographs (made with a diffusion transfer process) that might be seen as “on-site” works. Mormura puts special emphasis on his shooting locations as places where he dwells and creates, and it is these sites that contain the essence of his art. We hope that you will refer to Morimura’s essay, in which he reveals some of the secrets behind his art, as you look at this exhibition.

In closing, I would like to make note of the fact that this is the second anniversary of the new ShugoArts in its current location in Roppongi’s complex665. It is with great pleasure that we mark this important milestone with a solo exhibition by Morimura Yasumasa. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincerest appreciation to all of ShugoArts’ supporters and artists.

ShugoArts, Summer 2018

On My Art, My Story, My Art History

1

It has been about 35 years since I began making art works based on self-portrait photographs. Some people have suggested that I foresaw the present state of contemporary photography (or an age in which everyone would be taking pictures and their lives). I do not reject this view, but to be honest, I am not entirely comfortable with a world in which everyone enjoys taking pictures of themselves. I have never liked appearing in front of people. And I have never considered taking pictures of myself and using them to promote myself as a carefree or enjoyable activity. On the contrary, since I was basically a social recluse, my self-portraits were a way of curing myself and forcing myself to go out into the world – a drastic, self-prescribed remedy.

We are definitely living in an age of self-portraits. And I am an artist who used a pioneering approach that predated this age, but I in no way feel as if the times have finally caught up with me. Although the current situation does have certain parallels with my approach, there is also something decidedly different about it.

2

A certain Japanese psychologist, whom I deeply revere (but who is regrettably no longer with us), once told me, “I’m just like you, I disguise myself as all kinds of different characters.” At first, I was stunned to think that he had a secret fondness for taking pictures of himself, but that was not really the case.

He was actually explaining how he dealt with his clients as a psychoanalyst.

According to the psychologist, he would deal with his clients by playing a different part depending on each person’s symptoms. In some cases, he would deal with them like a father, and in other cases, he would deal with them like a mother. Simply put, he would take on all kinds of roles in his dialogues with them. But he said it was even more important for him to turn the entire space into a kind of virtual reality. In other words, these dialogues were not like actual events that took place in the real world; they took place in imaginary settings that were controlled by the psychologist. So even if the psychologist succeeded in getting the client to make an important admission by playing the part of their lover, he would never actually become their lover.

The psychologist explained this type of performance and control to me: “In my mind, I imagine a kind of theater or stage where many different plays might unfold. Next, I ask the client to appear there, play a certain part, and talk about various things. And then I also appear in a role that suits the client’s part. Isn’t there a small similarity between your art and this kind of psychoanalysis?”

I whole-heartedly support this psychologist’s way of thinking.

3

The camera is a mirror-like medium that brings another one of my faces to the surface.

4

Although I was born in Japan after the end of the Pacific War and after the country had come under the control of the Allied Forces, my mentality was shaped by a host of contradictions. On the one hand, I was influenced by traditional Japanese culture dating back before the war. But on the other hand, I am someone who was deeply influenced by the sudden surge of Western culture (particularly by America’s new culture), which negated Japanese traditional culture after the war. This explains why I have such a complicated love-hate relationship with Western culture, which came to me by way of America and American culture. These feelings of love and hate are key ingredients in the flavor of my works, and in recent years, they have become even stronger.

Needless to say, Japan, America, and the rest of the world have changed significantly since then. It has gotten to the point where you might well ask what terms like “postwar” and “prewar” mean, and whether at this point in time, they are valid means of understanding the period. Today, things like anime, Japanese food, and ninja are touted as Japanese culture, and the economic benefits are such that the Japanese government has accepted these things with open arms. I will refrain from commenting on the matter here, but since I am a person who might seem lighthearted but in certain instances can also be very tough, I remain obsessed with the theme of postwar Japan and am determined never to abandon it.

5

I have a desire to reconstruct history with my own hands. This does not mean that I want to rule history. On the contrary, I have no interest in becoming a ruler. Instead, by resisting the push to view history as accepted fact, I set out to destroy its authority. This impulse is probably similar to that of a child who likes to destroy his or her toys. When children get toys from adults, they often refuse any instruction about the proper way to play with them. Instead, they break them and enjoy putting them together exactly as they please, creating a “kid’s kingdom” that they are satisfied with. You might say that my artistic expressions are an extension of these childhood acts of destruction and recreation.

To me, a self-portrait is not a tool for presenting or promoting myself. It is more like an expression of pleasure at having devised an ingenious plan and remaking history with my own hands.

I also have the feeling that this handmade approach has something in common with my approach to self-portraits. I select and use images of notable historical figures as my materials to create a “handmade history of the human race and art” (to be utterly blunt about it). This means that it is not necessary for me to completely identify with the person who serves as my theme.

But there is a very subtle line, and unless I can identify in some way with the person, the work ends up being little more than a facial caricature (along the lines of “as long as there’s a resemblance, it’s fine”).

The other person and I are different entities. But if I do not feel the other person inside of me or feel myself inside of them, there is no way for us to understand each other. If the common sense that flows between us is a way of identifying with the other person, then it is absolutely indispensable to making a self-portrait. You might even go so far as to say that without common sense or identification, the game is up. You might think of this vital element as a kind of secret or trick of the self-portrait trade. I am convinced that unconsciously coming to this realization fairly early on has enabled me to continue making self-portraits for all of these years.

Morimura Yasumasa, August 1, 2018

MORIMURA Yasumasa, Study for Portrait (Van Gogh), 1985 Diffusion transfer process, 14.7×10.7cm

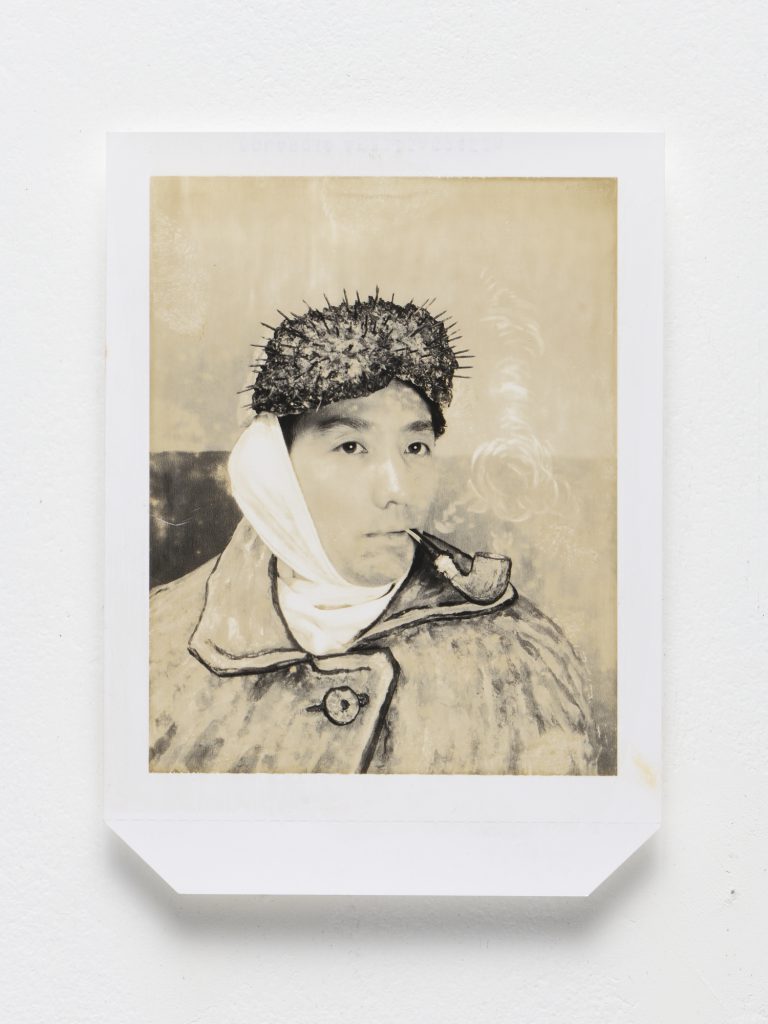

MORIMURA Yasumasa, Wearing Issei, 1996 Diffusion transfer process, 13.1×10.2cm

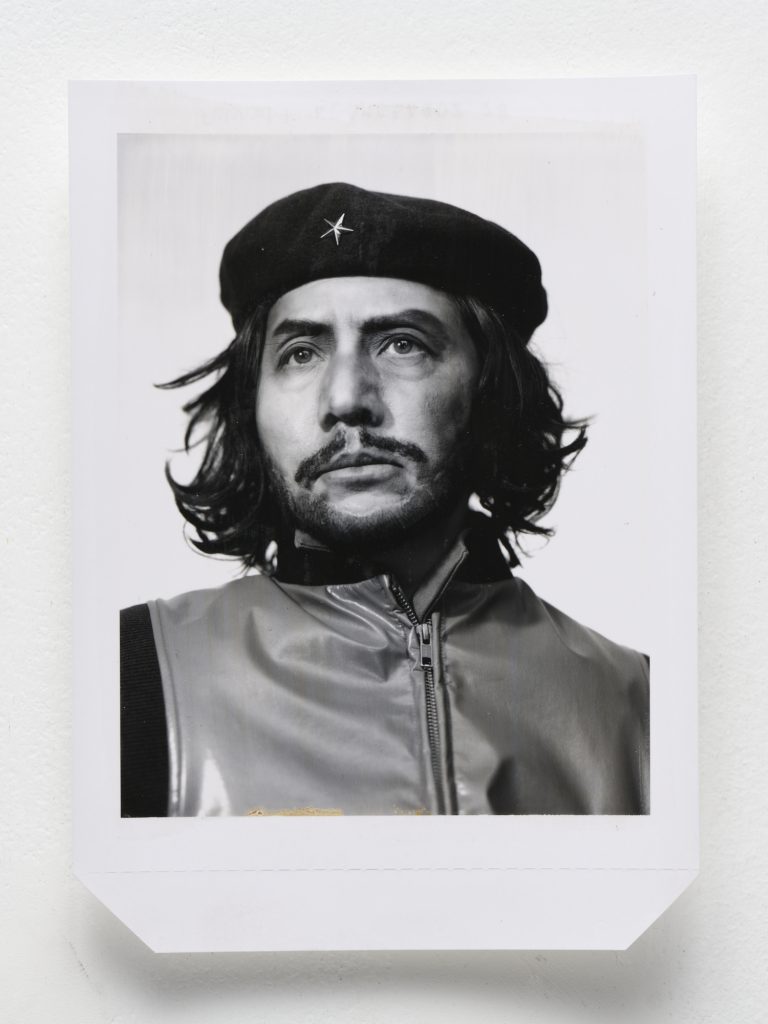

MORIMURA Yasumasa, Distant Che Guevara, 2007 Diffusion transfer process, 14.7×10.7cm