Artistic creation is a demand for unity and a rejection of the world. But it rejects the world on account of what it lacks and in the name of what it sometimes is. Rebellion can be observed here in its pure state and in its original complexities. Thus art should give us a final perspective on the content of rebellion.¹

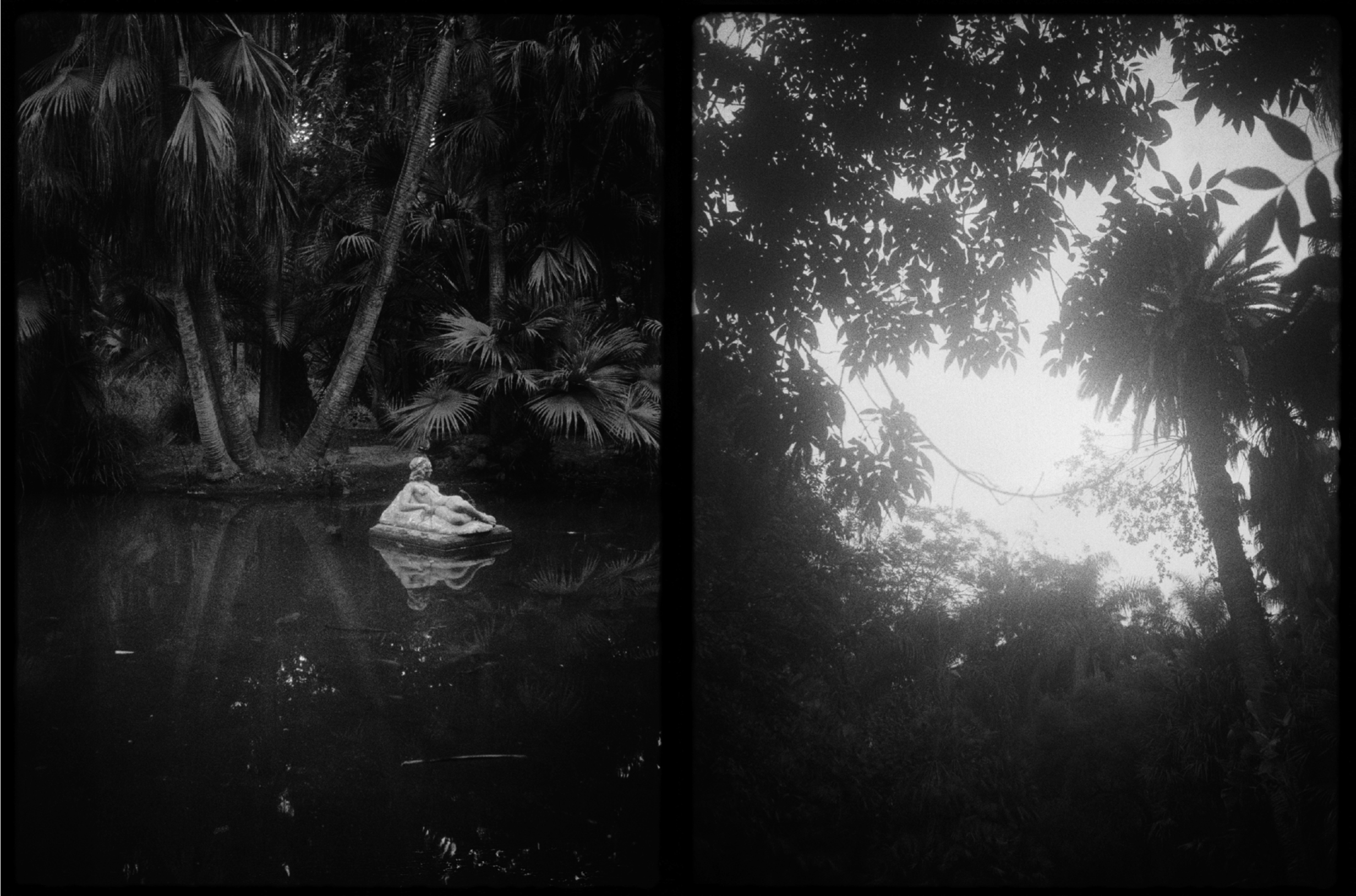

Albert Camus (1913–1960) was born in French colonial Algeria, his other homeland being France, that of the father he lost at a young age. Living through the violent upheavals of the 20th century, in his writings Camus cast an unflinching gaze on the absurdity of human fate, persistently addressing the questions of authentic rebellion and justice, and exploring the nature of human coexistence. Through his works Camus called (and struggled) for a pure dignity devoid of violence and authority, in which all people receive the same light and blessings of nature, and enjoy the same freedom. By travelling in the places, and the history, in which Camus lived and breathed, and which served as the sources of his creativity, through images from the author’s beloved Algeria and France and conversations with the people there, my aim was to assemble an exhibition addressing the notion of a universal, radiant love. Responding in my work to events of bygone eras, and the dark shadows now engulfing Europe, Japan and the world once again, I hoped to encourage viewers to turn their thoughts to the nature of human “being.”

The Neither Victims nor Executioners series of essays around which Dialogue with Albert Camus revolves made a powerful impression on me, in Cold War America at the time. Camus’ essays pointed to the nascent totalitarianism following the dropping of the atomic bombs in 1945 and the drawing of Cold War lines between east and west, and suggested a new beginning for our century, hitherto one of fear and dread dominated by the principle of the end justifying the means.

In them, Camus poses the fundamental question, “Do you, or do you not, directly or indirectly, want to be killed or assaulted?” ² If the answer is “no” one must refuse to be executioners, refuse to legitimise the taking of human lives. Have the times in which Camus lived, and the wars of our predecessors, set us on a path toward greater peace? The truth that Camus spent his life seeking—dignified rebellion and justice as authentic individuals, pure in their loyalty—is an eternal challenge for humanity. Sensing the importance, in today’s turbulent times, of pursuing—pivoting on Camus’ works and how he lived his life—the fundamental meaning of “existence and love as a human being possessed of life”, my hope is that the works in Dialogue with Albert Camus will encourage a dialogue across wide-ranging topics and people.

Tomoko Yoneda

1. Albert Camus, The Rebel.© Édition GALLIMARD, a revised and complete translation by Anthony Bower, 1st Vintage International ed.

2. Albert Camus, “Le siècle de la peur” in Camus à Combat, (c) Éditions GALLIMARD, translation by Dwight Macdonald, New Society Publishers